John Sayles’ Eight

Men Out, the story of the 1919 Chicago “Black Sox” scandal, is, on the one

hand, an odd outlier compared to the rest of his work, and on the other,

somewhat right in line with his plight of the working man sensibility. I’ve

always been a great admirer of Sayles’ films. I especially enjoy the fact that

he can make films illustrating the challenges of capitalism for laborers

without being preachy or overtly socialist. He’s the more toned down American

version of Ken Loach. In that respect, Eight

Men Out fits right in because his version of the story, which is based on

the book by Eliot Asinof, focuses more on the accused players as put-upon

contracted laborers in thrall to a greedy owner who exploits their talents for

financial gain. But amid his full body of work as writer and director it stands

out as one of only two films he adapted from source material. So while he’s

chosen to focus on the aspects that do appeal to him as a storyteller, the crux

of the film is that it’s a historical sports movie, standing very much apart

from his other work.

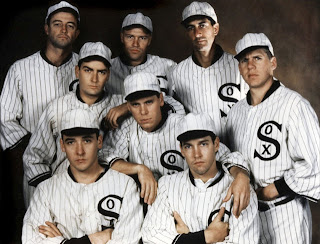

Sayles culled together an impressive pool of young talent

to portray the famed eight disgraced ballplayers. Sayles regular David

Strathairn is star pitcher Eddie Cicotte, depicted here as an honest man put

into a dishonest position out of necessity to get what seems owed to him.

Michael Rooker plays Chick Gandil, the guy whose connections to underworld

figures allowed the gamblers entrance to make their proposal. He’s one of the

two ballplayers depicted essentially as the heavies. The other is Don Harvey as

Swede Risberg. Newcomer D.B. Sweeney brings a goofy aw-shucks performance to

the role of “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, the most well-known of the eight. John

Cusack and Charlie Sheen were at the height of the 80s popularity when they

were cast as Buck Weaver and Happy Felsch, the latter of whom just wants to

please those around him and the former the most honest, a man who knew about

the fix, but asserts never to have taken a dime nor participated in throwing

games (his batting average and lack of errors in the series support his claim).

There’s so much to tackle in the story that Sayles’

screenplay can’t possibly encompass all the details to the point needed to

present a full understanding of what transpired. It’s fairly well accepted that

back in those days, the players, who were not yet represented by a union, made

very little money in comparison to what they were providing on the field in

terms of entertainment and ticket sales. The owners were the fat cats and

Clifton James as White Sox owner Charles Comiskey is shown to be ungracious,

greedy, and callous. So you have the conflict between players and owner, which

is itself the age-old battle between feudal lords and hired hands. But then you

throw in the conflict on the field, which may have been even greater, between the

uneducated players, mostly from the south, and the guys who’d been to college.

They play great ball together, but there’s animosity directed from the likes of

Risberg, Gandil, and Felsch toward players like Ray Schalk and Eddie Collins –

guys who were either college educated or from the north.

As to the question of how the fix all came together and

why, the questions are superficially answered, but good luck trying to figure

it all out from a single viewing without footnotes and historical documents. If

you don’t already know who the major and minor characters are, you might get

lost. There are the gamblers played by Christopher Lloyd, Richard Edson, and

Kevin Tighe. Arnold Rothstein is famously remembered as the man who arranged

the fix, but here he’s just a man with the financial backing to get it done.

Michael Lerner is one of several impressive actors in small roles in the film.

Along with Lerner there’s also John Mahoney as the stolid Sox manager Kid

Gleason, a man who suspects something, but trusts his boys to do the right

thing. And then sort of inexplicably tossed into the mix are Studs Terkel and

Sayles himself as journalists Hugh Fullerton and Ring Lardner. They are sort of

omnipresent, always commenting on the proceedings like a Greek chorus whose job

is to keep the uninitiated in the audience abreast of the subtleties of the

plot. There remarks to one another are of a sarcastic nature and never fit well

into the rhythm of the film. They feel tacked on and not anything at all like

the tight writing Sayles normally commits to.

No comments:

Post a Comment